Fathers Matter Research and M&E

Fatherhood: it’s complicated

In South Africa, the majority of children grow up in homes without fathers. The nuclear family, as defined by Western culture (mom, dad and children), is not the norm. Unemployment is prevalent and the ability to earn money is often limited. Men are expected to provide financially despite their employment status and women are seen as the primary caregivers. Many men are often absent within the home and in caregiving roles. This is because they either do not live in the same house as their children (physical absence) or they are unable to be involved or engaged in their day-to-day routines and experiences (emotional absence) — or both. As a result, the reality for a large number of South African children is one of father absence.

A lack of positive and active presence of men in their lives puts children at risk. Global literature highlights that children who grow up without such fathers or father-figures are at an increased risk of becoming victims or perpetrators of violence, mental illness, substance abuse, teenage pregnancy and poor educational and economic outcomes. It’s important to note, however, that this is a risk, not a foregone conclusion. It’s also not to say that the role of single mothers is appreciated any less.

“It is a very sad life, because your father was not there.”

What the research shows

Heartlines, the Centre for Values Promotion, is developing a set of interventions that promote the positive presence of fathers/men in the lives of children. These interventions are based on the findings of a formative research process that was set up to unpack what it means to be a father in the South African context, as well as the perceived barriers and challenges to active participation from fathers, and the impact of this absence. The Heartlines Fathers Matter research report captures the voices of the research participants themselves and provides insights into their reflections, beliefs, behaviours and attitudes.

What the research showed most strongly is that, in South Africa, having the means to provide financially is a defining component of fatherhood. Fathers that were able to provide financially were seen as “good”, whereas those that were unable to provide were simply “not good enough”.

Communities, mothers and extended families reinforced the idea of fathers as financial providers, irrespective of their employment status; resulting in participants equating fathers to “ATMs”, where financial provision was the means for entry and ongoing access to participation with their children.

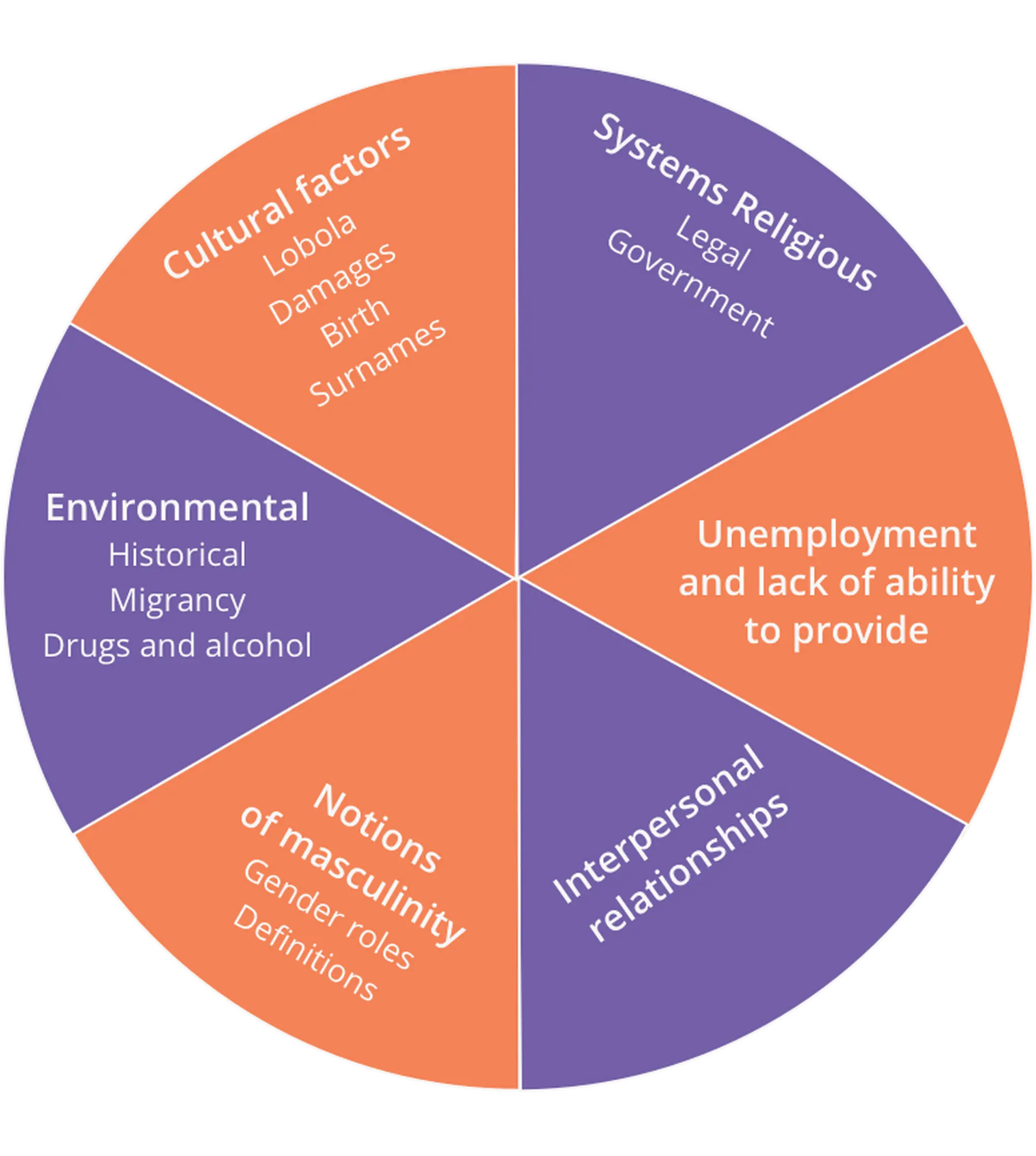

Barriers to father involvement

Key barriers that result in father absence include:

The research further showed that, despite the reality of father absence, individuals wanted more when it came to the role their fathers played in their lives. There was a yearning for connection, attachment and engagement with their fathers.

“…it’s difficult, when you see other children with their father and you just wish your father was there…”

In addition, there were fathers who made a conscious decision to be different. Men who, despite not having a father to model their behaviour from, chose to actively engage with, participate in, and care for their children. These fathers understood that their positive presence was crucial to their children’s emotional, physical and academic outcomes.

“…you can see other children taking photos with their fathers and wish that if only you were in the photos.”